Do you know… That in 1929 a proposal was made to build a Floating Airport between New York and Bermuda?

By Horst Augustinovic

By 1929 more than 400,000 passengers were traveling the world by air. While many saw a great potential for rapid air transportation of mail, cargo, and passengers, the reality was that no airplane was able to fly economically beyond a 500-mile range at that time. Although Charles Lindbergh had crossed the Atlantic two years earlier, doing so with a load of passengers and cargo was still in the distant future.

Edward Armstrong, an engineer who specialized in aviation design and construction, and an authority on transoceanic flight, was convinced that “in any type plane, now developed or proposed, equipped for ocean flying, it will require almost an engineering miracle to extend useful payload to a thousand miles. Fundamentals of design and performance fix very definite limits to economic flight distance – distances that fall very short of spanning either the Atlantic or Pacific.”

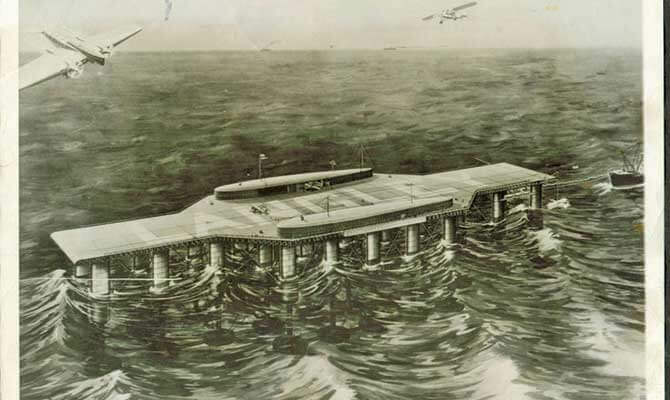

Armstrong’s solution to the problem: a seadrome that would be a “floating landing deck” – an anchored airport and refueling station. It would ride high above the waves, moored at one end so as to trail the wind and be big enough to permit the landing and takeoff of most planes. Supported by tubular columns 70 feet or more above the surface, waves would pass through underneath, with the columns themselves terminating in ballast tanks 100 feet below the surface.

In 1926 Armstrong incorporated the Seadrome Development Company and, with the enthusiasm created by Lindbergh’s flight, raised enough money to move his research out of the laboratory. By early 1929 he envisioned service between America and Europe, using eight seadromes, with planes leaving hourly in both directions and a flying time of 30 hours. To demonstrate the practicality of the scheme, Armstrong planned to put into place one seadrome connecting New York City with Bermuda.

Flying time for each leg would be approximately three hours. Passenger service would be scheduled only during daylight hours, but a night mail plane would deliver the New York newspapers for sale in Bermuda in the morning. For those wishing an overnight experience on the seadrome, there would be a hotel with 40 guest rooms, and during the day a café, a lounge, and other facilities would serve up to 350 people. 1,100 feet long and 340 feet wide, the New York-to-Bermuda seadrome was estimated to weigh about 50,000 tons.

In the summer of 1929, Armstrong built a 35 feet long scale model and anchored it in the Choptauk River near Cambridge, Maryland. He tested it in a variety of wind, wave, and current conditions and concluded that a full-scale seadrome could survive 280-mile-per-hour winds and waves up to 144 feet high. He announced that construction of a full-size seadrome would begin in the Chesapeake in December, and the finished structure would be towed to sea the following summer.

Unfortunately his announcement coincided with the New York Times headline PRICES OF STOCKS CRASH IN HEAVY LIQUIDATION, TOTAL DROP OF BILLIONS. It was the beginning of the Great Depression and potential investors found nothing reassuring about seadromes or the stock market. It was also the end of the scheme to build a seadrome between New York and Bermuda.

The Bermuda Trade Development Board had earlier offered a $25,000 prize for the first direct flight to Bermuda, however, aeronautical experts considered it too hazardous and the prize offer was withdrawn. Still an attempt was made a few months after the collapse of the seadrome scheme – on April 1st 1930 of all dates – by a Stinson monoplane equipped with pontoons and called Pilot, piloted by William Alexander with Lewis Yancey as navigator and Zeh Bouck as radio operator, to fly non-stop to Bermuda.

Sixty miles north of Bermuda Pilot unfortunately ran out of fuel and had to land at sea. After refueling the following morning, Pilot finally made it to Murray’s Anchorage – the first plane to (almost) fly non-stop to Bermuda. Having been tossed around for a night on the open Atlantic, and after receiving a $1,000 cheque each from the Trade Development Board at a special dinner at the Hamilton Princess, the three aviators were in no mood to attempt a return flight to New York. Instead, they and Pilot returned to New York on the steamship Arcadian.