By Dr. Edward Cecil Harris, MBE, JP, PHD, FSA

In the nineteenth century, Bermuda was of interest to a new breed of scientists, being geologists who studied the formation of the Earth. A phenomenon (‘something that can be observed and studied and that typically is unusual or difficult to understand or explain fully’) that attracted the interest of such scholars visiting Bermuda at that period was the ‘travelling sands’ or ‘sand glaciers’ of the south shore.

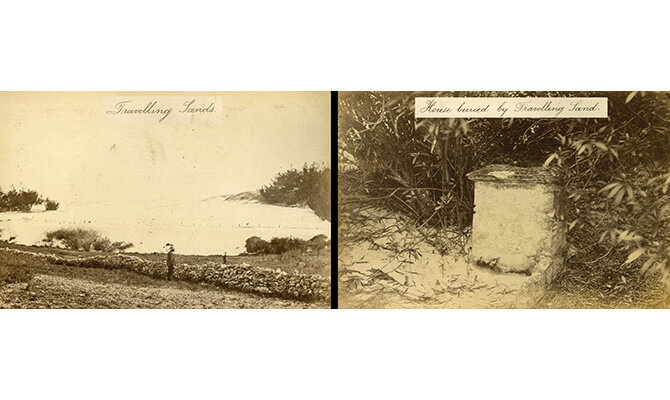

Of late, a wonderful pre-photography image of the mid-1830s by Dr. Johnson Savage MD has given us a vivid impression of one area of such dunes. In that view, the shifting sands have leapt over a boundary wall and are in the process of devouring a cedar forest. Other sand glaciers were recorded by photography, when HMS Challenger visited Bermuda in 1873.

Now somewhat quiescent, the travelling sands were very active at times during the 1800s, and Bishop Inglis from Halifax observed the following on Monday, 25 May 1835:

‘Dr. Hunter took us in his boat, under a comfortable awning, first to Castle Island, between three and four miles, where we landed and went through the ruins of this ancient defence of Bermuda. The scenery is all-beautiful. We next rowed along the shore to Tucker’s Town, which legend says was once considerable, but now lies buried under sand. All this may be doubted. Formerly there were more houses than at present exist in the neighbourhood, and many persons were injured by the accumulation of sand to the depth of 6, 8, and even 10 and 12 feet in some place, and probably this discouraged occupation in the neighbourhood.’

Bermudian hydrogeologist, Mark Rowe, has kindly commented on the travelling sands: ‘Notwithstanding their current state of relative stability, Bermuda’s coastal dunes exhibited pulses of mobility in the 19th century at several locations along the south shore. An example of such activity at Elbow Beach is depicted in Johnson Savage’s “Sand Hills” watercolour dating from 1833 to 1836. Reports, from about the same time, describe the burial of several houses by dunes at Tucker’s Town and of at least one house near Elbow Beach. At the latter location, dunes, which climbed to a height of 180 feet and advanced at rates of 10 to 20 feet per year, as documented by Lieut. Richard Nelson in 1837, were still active when visited, as an object of scientific curiosity, by British scientists of the Challenger Expedition in 1873. Later still, geologist Angelo Heilprin (1887) observed dunes at Elbow Beach and Tucker’s Town which he described as “great tongues of sand” and “sand glaciers…stealthily encroaching on hilltops of the interior and burying everything”.’

‘These observations of “modern’, albeit relatively minor, dune activity provide a valuable insight into the formation of the Bermuda Islands, which are for the most part constituted of lithified (hardened) sand dunes. In fact, the geological term “eolianite”, meaning a rock created by the cementation of eolian (wind-blown) sands, was coined in Bermuda in 1931 by geologist Robert Sayles.’

Thus, Bermuda is but, geologically speaking, a house of sand in the Western North Atlantic.

First featured image: Harris Sand Dunes. In 1872, HMS Challenger visited Bermuda: its photographer recorded the ‘Travelling Sands’ of Paget Parish and all that was left of a buried house in a sand dune (Fay and Geoffrey Elliott Collection, National Museum).

Second & Third featured image: Harris Sand Dunes. About 1835, Dr. Johnson Savage executed a painting of the travelling sands and in the lower 2014 picture by Mark Rowe, a part of the area thought to be depicted in the Savage image is found at the eastern end of Elbow Beach (Johnson Savage MD Collection, National Museum).

Fourth featured image: Harris Sand Dunes. In this rock face, the trunk and some fronds of a buried palmetto palm were captured on camera in 2012 by Mark Rowe at Hungry Bay, Paget, preserved as a hole and impressions in the Bermuda limestone.